0. What’s the Story Behind the Spelling?

- There are 8 English ways to spell the Festival of Lights: Chanukah, Hanukah, Channukah, Hannukah, Chanukkah, Hanukkah, Chanuka, Hanuka.

- The ninth way is “janukah”, because in Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) the “j” makes the “ch” sound (plus "Khanike" in Yiddish). — There are only two ways to spell the holiday in Hebrew, though: חנוכה, and חנכה.

- The name means “(re)dedication”, since the Temple was rededicated after the Syrian-Greeks trashed it and put in a statue of Zeus.

- The ninth way is “janukah”, because in Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) the “j” makes the “ch” sound (plus "Khanike" in Yiddish). — There are only two ways to spell the holiday in Hebrew, though: חנוכה, and חנכה.

- The name means “(re)dedication”, since the Temple was rededicated after the Syrian-Greeks trashed it and put in a statue of Zeus.

1. What’s the Story Behind Dreidels?

- Dreidels are a 4-sided top with the Hebrew letters nun, gimel, hey, and shin (or pey in Israel) on them.

- They are used to play a gambling game.

- The letters stand for Nes Gadol Haya Sham/Po - a great miracle happened there/here (depending on whether you are outside or inside Israel)

- The story that is told is that the Jews would pretend to be gambling to fool the Syrian-Greeks since learning Torah was illegal.

The actual historical origin of dreidels is the Irish/English Christmas game of Totum (meaning “All” in Latin) dating back to 1500 CE.

- By 1720 called “teetotum”

- Original letters - T - Totum (Take all), A - Aufer (Take from the pot), N - Nihil (Nothing), D - Depone (Put into the pot)

- By 1801 new letters - T = Take All, H = Half, P = Put down, N = Nothing

- German equivalent (now called “Trundl”) - G = Ganz (all), H = Halb (half), N = Nichts (Nothing), S = Stell ein (put in) [Letters look familiar?]

- Yiddish equivalent (now called “dreidel”, “a little spinning thing”, from German word “Drehen”, meaning “spin”) - G - Gants (all), H - Halb (half), N = Nit (not = nothing), S = Shtel Arayn (put in)

- Other regional names in use until the Holocaust - Goyrl (destiny) and Varfl (a little throw)

- Hebrew name - Sevivon (little spinner)

- Name coined by Itamar Ben-Avi, son of Eliezer Ben-Yehudah and first native-born Hebrew speaker (born 1882), when he was 5

- “I Have a Little Dreidel” was written in 1927 by Samuel Goldfarb, a Tin Pan Alley composer (and younger brother of Israel Goldfarb, composer of “Shalom Aleichem”, “Magen Avot”, and more). The song took off in the 1950s.

- There are many other explanations as to why we use dreidels on Chanukah. These developed once the dreidel was already a Chanukah toy (so they are post-de-facto).

- Gematria of 4 letters = 358 = Mashiach - spinning as an act of Messianic hope

- 358 = nachash = serpent = toppling evil

- 358 = Hashem Melech Hashem malach Hashem yimloch (G-d reigned, reigns, and will reign)

- Toppling = the small army toppling the strong army

- Nebuchadnezzer/Babylon, Haman/Persia, Gog/Greece, Seir/Rome, each of which eventually fell (according to Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Shapiro of Dinov, in “B’nai Yissachar”)

- N = Nefesh (soul), G = Guf (body), S = Seichel (mind), H = Hakol (everything) - these 4 components are blended into an indistinguishable oneness

- The Jews played with dreidels during the Hadrianic persecutions to fool the soldiers into thinking that since they gambled they couldn’t be interested in studying Torah; the letters were written then to give hope that G-d would help them outlast the Roman Empire just like G-d helped them against the Syrian-Greeks.

- Don’t know how our luck in life will fall, but everything revolves around the central point of G-d

- The key take-away here is that the Syrian-Greeks wanted us to take on their culture and lose ours, and the dreidel represents taking on another culture and making it part of ours.

- They are used to play a gambling game.

- The letters stand for Nes Gadol Haya Sham/Po - a great miracle happened there/here (depending on whether you are outside or inside Israel)

- The story that is told is that the Jews would pretend to be gambling to fool the Syrian-Greeks since learning Torah was illegal.

The actual historical origin of dreidels is the Irish/English Christmas game of Totum (meaning “All” in Latin) dating back to 1500 CE.

- By 1720 called “teetotum”

- Original letters - T - Totum (Take all), A - Aufer (Take from the pot), N - Nihil (Nothing), D - Depone (Put into the pot)

- By 1801 new letters - T = Take All, H = Half, P = Put down, N = Nothing

- German equivalent (now called “Trundl”) - G = Ganz (all), H = Halb (half), N = Nichts (Nothing), S = Stell ein (put in) [Letters look familiar?]

- Yiddish equivalent (now called “dreidel”, “a little spinning thing”, from German word “Drehen”, meaning “spin”) - G - Gants (all), H - Halb (half), N = Nit (not = nothing), S = Shtel Arayn (put in)

- Other regional names in use until the Holocaust - Goyrl (destiny) and Varfl (a little throw)

- Hebrew name - Sevivon (little spinner)

- Name coined by Itamar Ben-Avi, son of Eliezer Ben-Yehudah and first native-born Hebrew speaker (born 1882), when he was 5

- “I Have a Little Dreidel” was written in 1927 by Samuel Goldfarb, a Tin Pan Alley composer (and younger brother of Israel Goldfarb, composer of “Shalom Aleichem”, “Magen Avot”, and more). The song took off in the 1950s.

- There are many other explanations as to why we use dreidels on Chanukah. These developed once the dreidel was already a Chanukah toy (so they are post-de-facto).

- Gematria of 4 letters = 358 = Mashiach - spinning as an act of Messianic hope

- 358 = nachash = serpent = toppling evil

- 358 = Hashem Melech Hashem malach Hashem yimloch (G-d reigned, reigns, and will reign)

- Toppling = the small army toppling the strong army

- Nebuchadnezzer/Babylon, Haman/Persia, Gog/Greece, Seir/Rome, each of which eventually fell (according to Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Shapiro of Dinov, in “B’nai Yissachar”)

- N = Nefesh (soul), G = Guf (body), S = Seichel (mind), H = Hakol (everything) - these 4 components are blended into an indistinguishable oneness

- The Jews played with dreidels during the Hadrianic persecutions to fool the soldiers into thinking that since they gambled they couldn’t be interested in studying Torah; the letters were written then to give hope that G-d would help them outlast the Roman Empire just like G-d helped them against the Syrian-Greeks.

- Don’t know how our luck in life will fall, but everything revolves around the central point of G-d

- The key take-away here is that the Syrian-Greeks wanted us to take on their culture and lose ours, and the dreidel represents taking on another culture and making it part of ours.

2. What’s the Story Behind Gelt?

- Gelt are foil-covered chocolate coins; they usually come in mesh bags and can be used when playing dreidel (as well as just eaten).

- “Gelt” is the Yiddish word for “money”

- It was originally actual money

- According to the Belzer Rebbe, given to all to blur the distinguishment between who needed tzedakah and who didn’t

- Connects to the coins minted by the Hasmoneans in the Chanukah story. Coinage began in 142 BCE and had a menorah on them. This was a tangible sign of independence (I Maccabees 15:5)

- Starting in 1958, Israel made commemorative Chanukah coins for use as gelt in dreidel games. The first one had the same menorah as the Hasmonean coins. In 1972 they made one with a Russian chanukiah, and in 1976 they made a Colonial chanukiah design on the coin. Each year (at least through 1990) they honor a different Jewish community around the world; see here for images: https://www.pcgs.com/news/menorah-coinage-of-israel

- Possibly inspired by the Purim customs of Mishloach Manot and Matanot LeEvyonim - giving gifts to friends and those in need

- According to Leah Koenig, “Chanukah” and “Education” share the same Hebrew root - חנכ

- In the 700s, poor students would go door to door to collect coins so they could keep studying.

- In the 1700s in Europe, children would be given coins to give to their usually-unpaid teachers on Chanukah (like tipping the postal carrier for Christmas)

- Later, children also got coins to encourage their studies, with the idea that these coins be set aside to fund future studies.

- Sholom Aleichem writes about children going house to house to collect gelt in the late 1800s in Eastern Europe.

- In the 1800s, poor Sephardic children would go door to door on Chanukah offering to burn sweet grasses to ward off the evil eye in exchange for some coins

- In the 1920s in America, the giving of “gelt” (ranging from a few coins to savings bonds) in greeting cards became more popular between friends

- To capitalize on this interest, in the 1920s Lofts (an American candy company) started producing gold-covered chocolate coins, also called “gelt” (like candy cigars)

- Rabbi Deborah Prinz, author of On the Chocolate Trail, connects these to “geld”, which were chocolate coins given to children in the Netherlands and Belgium for the St. Nicholas holiday in early December

- Chocolate Maccabees and chocolate latkes were not as popular as chocolate gelt.

- Most chocolate gelt today is produced by the Elite and Carmit companies in Israel

- Today, some children still receive actual money that they must use to give to a tzedakah-designation of their choosing.

- The organization “Fifth Night” (fifthnight.org) tries to spread this practice and centralize it to be on the 5th night of Chanukah.

- Today you can also buy Fair Trade Gelt so others don’t have to suffer for our enjoyment of freedom - http://fairtradejudaica.org/product/kosher-chanukah-gelt/

- “Gelt” is the Yiddish word for “money”

- It was originally actual money

- According to the Belzer Rebbe, given to all to blur the distinguishment between who needed tzedakah and who didn’t

- Connects to the coins minted by the Hasmoneans in the Chanukah story. Coinage began in 142 BCE and had a menorah on them. This was a tangible sign of independence (I Maccabees 15:5)

- Starting in 1958, Israel made commemorative Chanukah coins for use as gelt in dreidel games. The first one had the same menorah as the Hasmonean coins. In 1972 they made one with a Russian chanukiah, and in 1976 they made a Colonial chanukiah design on the coin. Each year (at least through 1990) they honor a different Jewish community around the world; see here for images: https://www.pcgs.com/news/menorah-coinage-of-israel

- Possibly inspired by the Purim customs of Mishloach Manot and Matanot LeEvyonim - giving gifts to friends and those in need

- According to Leah Koenig, “Chanukah” and “Education” share the same Hebrew root - חנכ

- In the 700s, poor students would go door to door to collect coins so they could keep studying.

- In the 1700s in Europe, children would be given coins to give to their usually-unpaid teachers on Chanukah (like tipping the postal carrier for Christmas)

- Later, children also got coins to encourage their studies, with the idea that these coins be set aside to fund future studies.

- Sholom Aleichem writes about children going house to house to collect gelt in the late 1800s in Eastern Europe.

- In the 1800s, poor Sephardic children would go door to door on Chanukah offering to burn sweet grasses to ward off the evil eye in exchange for some coins

- In the 1920s in America, the giving of “gelt” (ranging from a few coins to savings bonds) in greeting cards became more popular between friends

- To capitalize on this interest, in the 1920s Lofts (an American candy company) started producing gold-covered chocolate coins, also called “gelt” (like candy cigars)

- Rabbi Deborah Prinz, author of On the Chocolate Trail, connects these to “geld”, which were chocolate coins given to children in the Netherlands and Belgium for the St. Nicholas holiday in early December

- Chocolate Maccabees and chocolate latkes were not as popular as chocolate gelt.

- Most chocolate gelt today is produced by the Elite and Carmit companies in Israel

- Today, some children still receive actual money that they must use to give to a tzedakah-designation of their choosing.

- The organization “Fifth Night” (fifthnight.org) tries to spread this practice and centralize it to be on the 5th night of Chanukah.

- Today you can also buy Fair Trade Gelt so others don’t have to suffer for our enjoyment of freedom - http://fairtradejudaica.org/product/kosher-chanukah-gelt/

3. What’s the Story Behind Chanukah Presents?

- Originally just coins were given as gifts to children on Chanukah

- American Jews only gave gifts to each other on Purim, as part of elaborate Mishloach Manot.

- In the late 1800s, Christmas became more commercialized and focused on buying/giving gifts instead of the religious aspects for many in America

- In the 1920s, advertisers (such as Colgate) began advertising their wares as suitable gifts for Chanukah in the Yiddish newspapers

- In the early 1940s, Chanukah-specific products start to be made (think Chanukah pot-holders and Chanukah greeting cards).

- In the late 1940s, Judaica wholesalers begin as the aftermath of the Holocaust makes American Jews feel that the future of world Jewry rests on their shoulders.

- In the 1950s, giving Chanukah gifts to children took off as child-psychologists and rabbis encouraged it as a way to make kids like being Jewish instead of sad about not having Christmas.

- In the 1980s, child-centered Chanukah items (like stickers and gelt-filled dreidels) really take off with the arrival of the Millenials.

- In the 1990s, Judaica wholesalers get Chanukah a spot on department-store shelves.

- Today, giving gifts on Chanukah is still more of an American thing.

- Some families today de-emphasize gift-receiving by setting aside one night for volunteering to help others, and/or saying that the money for one night’s presents will instead be given to an organization the family determines together

- American Jews only gave gifts to each other on Purim, as part of elaborate Mishloach Manot.

- In the late 1800s, Christmas became more commercialized and focused on buying/giving gifts instead of the religious aspects for many in America

- In the 1920s, advertisers (such as Colgate) began advertising their wares as suitable gifts for Chanukah in the Yiddish newspapers

- In the early 1940s, Chanukah-specific products start to be made (think Chanukah pot-holders and Chanukah greeting cards).

- In the late 1940s, Judaica wholesalers begin as the aftermath of the Holocaust makes American Jews feel that the future of world Jewry rests on their shoulders.

- In the 1950s, giving Chanukah gifts to children took off as child-psychologists and rabbis encouraged it as a way to make kids like being Jewish instead of sad about not having Christmas.

- In the 1980s, child-centered Chanukah items (like stickers and gelt-filled dreidels) really take off with the arrival of the Millenials.

- In the 1990s, Judaica wholesalers get Chanukah a spot on department-store shelves.

- Today, giving gifts on Chanukah is still more of an American thing.

- Some families today de-emphasize gift-receiving by setting aside one night for volunteering to help others, and/or saying that the money for one night’s presents will instead be given to an organization the family determines together

4. What’s the Story Behind the Chanukah Story?

- In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Land of Israel on his way to ruling from Greece to India.

- When he died, his empire was divided between his generals. Israel was controlled by Ptolemy, in Egypt.

- In 198 BCE, the Syrian Seleucids gained control of the Land of Israel.

- In order to establish Israel as a buffer zone against Ptolemaic Egypt, Antiochus IV sought to culturally tie the Jews into his empire by getting rid of Judaism.

- This led to a revolt in 164 BCE, led by the Hasmoneans under Judah Maccabee.

- According to the 1st and 2nd Books of Maccabees, the Jews managed to get the Syrian-Greeks to withdraw, giving the Jews a chance to clean up and rededicate the Second Temple. As part of this process, they made a new menorah, since Antiochus had the original one removed to Syria (I Maccabees 1:23), and lit it.

- According to I Maccabees 4:54 (written shortly after the events occurred), the dedication ceremony took 8 days. Perhaps this is because the original dedication ceremony of the First Temple under King Solomon took 8 days.

- According to II Maccabees 10:9 (written shortly after the events occurred), the dedication ceremony took 8 days because Sukkot is 8 days and they had not been able to celebrate it during the fighting.

- According to Pesikta Rabbati 2:1(written about 600 years after the events occurred), the Jews found 8 spears stuck in the ground by the Temple. They hollowed out the ends and used them as a make-shift menorah.

- According to the Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 21b:10 (written about 600 years after the events occurred), the Jews only found enough sealed oil to last 1 day, but a miracle occurred and it lasted 8 days until more oil could be produced.

- This “miracle”, if it occurred, was not considered noteworthy enough to make it into the contemporaneous accounts of the Books of Maccabees.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because their descendants had a fratricidal civil war which led to Rome being invited into the Land of Israel and eventually taking over.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because they insisted on being both kings and high priests simultaneously.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because they later killed many Pharisees (the forerunners of the Rabbis).

- The Rabbis also had an agenda of bringing G-d into holidays where G-d was not as apparent, such as Purim.

- The Rabbis also had an agenda of tamping down on militarism, so that there wouldn’t be a rebellion against the Persians like Mar Zutra’s revolt against the radical Persians who were oppressing Christians, conservative Persians, and Jews (495 CE).

- Note that if the Jews were using a make-shift menorah, as the Pesikta Rabbati claims, then 1 day worth of oil for the regular menorah could easily last 8 days in a menorah that doesn’t hold as much oil (Kippah tip to Miron Hirsch).

- When he died, his empire was divided between his generals. Israel was controlled by Ptolemy, in Egypt.

- In 198 BCE, the Syrian Seleucids gained control of the Land of Israel.

- In order to establish Israel as a buffer zone against Ptolemaic Egypt, Antiochus IV sought to culturally tie the Jews into his empire by getting rid of Judaism.

- This led to a revolt in 164 BCE, led by the Hasmoneans under Judah Maccabee.

- According to the 1st and 2nd Books of Maccabees, the Jews managed to get the Syrian-Greeks to withdraw, giving the Jews a chance to clean up and rededicate the Second Temple. As part of this process, they made a new menorah, since Antiochus had the original one removed to Syria (I Maccabees 1:23), and lit it.

- According to I Maccabees 4:54 (written shortly after the events occurred), the dedication ceremony took 8 days. Perhaps this is because the original dedication ceremony of the First Temple under King Solomon took 8 days.

- According to II Maccabees 10:9 (written shortly after the events occurred), the dedication ceremony took 8 days because Sukkot is 8 days and they had not been able to celebrate it during the fighting.

- According to Pesikta Rabbati 2:1(written about 600 years after the events occurred), the Jews found 8 spears stuck in the ground by the Temple. They hollowed out the ends and used them as a make-shift menorah.

- According to the Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 21b:10 (written about 600 years after the events occurred), the Jews only found enough sealed oil to last 1 day, but a miracle occurred and it lasted 8 days until more oil could be produced.

- This “miracle”, if it occurred, was not considered noteworthy enough to make it into the contemporaneous accounts of the Books of Maccabees.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because their descendants had a fratricidal civil war which led to Rome being invited into the Land of Israel and eventually taking over.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because they insisted on being both kings and high priests simultaneously.

- It is important to know that the Rabbis who wrote the Babylonian Talmud did not like the Hasmoneans because they later killed many Pharisees (the forerunners of the Rabbis).

- The Rabbis also had an agenda of bringing G-d into holidays where G-d was not as apparent, such as Purim.

- The Rabbis also had an agenda of tamping down on militarism, so that there wouldn’t be a rebellion against the Persians like Mar Zutra’s revolt against the radical Persians who were oppressing Christians, conservative Persians, and Jews (495 CE).

- Note that if the Jews were using a make-shift menorah, as the Pesikta Rabbati claims, then 1 day worth of oil for the regular menorah could easily last 8 days in a menorah that doesn’t hold as much oil (Kippah tip to Miron Hirsch).

5. What’s the Story Behind Candles?

- Many cultures have a candle-lighting holiday in the winter, bringing light to the darkness, such as the Zoroastrian winter solstice holiday of Chaharshanbe Suri.

- In the Babylonian Talmud, one explanation for Chanukah is that Adam saw the light lasting for fewer and fewer hours in winter but then increasing in length, and so he made a holiday to celebrate the return of the light (Avodah Zara 8a:7-8)

- In 1st and 2nd Maccabees (around 150 BCE), the story of Chanukah includes rekindling the menorah as part of the rededication of the Temple.

- Josephus (70 CE) says that Chanukah is called “Lights”, though he’s not sure why.

- The oldest Chanukah lamp that was found was from the 100s CE in a cave outside Jerusalem. It was a piece of limestone carved into a square with eight slots for holding olive oil and fiber wicks.

- In the Mishnah (200 CE), the only mention of a “Chanukah lamp” is in the context of whether a shopkeeper is liable if a camel passing by with flax burns down their shop (answer: Yes, if the shopkeeper had a lamp outside, No, if the lamp outside was a Chanukah lamp - Bava Kama 6:6). This shows that the custom was so widespread that it didn’t warrant explanation.

- The Temple had a 7-branched menorah (also the modern Hebrew word for “lamp”). A Chanukah menorah is technically called a “chanukiah”.

- The chanukiah in Mishnaic times was made from clay or stone, and had a hole for olive oil and another hole for a wick. One would use multiple lamps as Chanukah progressed.

- In the Babylonian Talmud (500 CE), it says that the reason we light candles is because there was only enough oil for one night but it lasted for eight nights. (Shabbat 21b). The Talmud also regulates which oils can be used (pretty much anything, including that which can’t be used on Shabbat), how many wicks to light (Shammai says start with 8 and go down to 1 since the days left are fewer, Hillel says to start with 1 and go up to 8 since we “increase in holiness” - Hillel wins), when to light (after dark but while people are still out and about in order to “publicize the miracle”), and where to light (outside, as is still the case in Israel, or at the window, in order to “publicize the miracle”, unless that’s a bad idea in which case inside on a table is fine).

- The Babylonian Talmud also said that one should not use the Chanukah lights for anything, but that it was OK to light another light (pre-electricity, one needed lights to see after dark). This later became the origin of the shamash (Shabbat 21b).

- Additionally, the Babylonian Talmud rules about the blessings to be said when lighting the chanukiah, that we say 3 on the first night and 2 on the other nights (Shabbat 23a). The blessing for Shabbat candles comes from the one for Chanukah candles, and is first recorded in the siddur of Amram Gaon (800s CE).

- The chanukiah in Talmudic times was also made from clay or stone, or sometimes metal, and had 8 holes for wicks.

- In the 1200s in Spain, chanukiot evolved again, with a back on it, eight dimples for oil, and a shamash for the first time (on a different plane from the others). These were meant to be hung on the wall.

- In medieval Germany it was popular to have an 8-pointed star chanukiah which hung from the ceiling (an example is in the Sarajevo Haggadah).

- In the 1800s, candles became mass-produced and thus affordable for the masses.

- In the 1940s, brass chanukiot are mass-produced.

- In the Holocaust (1933-1945, when money was scarce and then freedom was scarcer), many Jews made chanukiot out of potatoes, a dab of butter, and a thread.

- In the 1960s, electric chanukiot are mass-produced (and onwards)

- Nowadays, technically one should light the Shammash, then say the blessings, then start lighting the candles, and while doing so sing “Hanerot Hallalu” (which comes from Sofrim 20:6, a text from the 700s CE).

- In the Babylonian Talmud, one explanation for Chanukah is that Adam saw the light lasting for fewer and fewer hours in winter but then increasing in length, and so he made a holiday to celebrate the return of the light (Avodah Zara 8a:7-8)

- In 1st and 2nd Maccabees (around 150 BCE), the story of Chanukah includes rekindling the menorah as part of the rededication of the Temple.

- Josephus (70 CE) says that Chanukah is called “Lights”, though he’s not sure why.

- The oldest Chanukah lamp that was found was from the 100s CE in a cave outside Jerusalem. It was a piece of limestone carved into a square with eight slots for holding olive oil and fiber wicks.

- In the Mishnah (200 CE), the only mention of a “Chanukah lamp” is in the context of whether a shopkeeper is liable if a camel passing by with flax burns down their shop (answer: Yes, if the shopkeeper had a lamp outside, No, if the lamp outside was a Chanukah lamp - Bava Kama 6:6). This shows that the custom was so widespread that it didn’t warrant explanation.

- The Temple had a 7-branched menorah (also the modern Hebrew word for “lamp”). A Chanukah menorah is technically called a “chanukiah”.

- The chanukiah in Mishnaic times was made from clay or stone, and had a hole for olive oil and another hole for a wick. One would use multiple lamps as Chanukah progressed.

- In the Babylonian Talmud (500 CE), it says that the reason we light candles is because there was only enough oil for one night but it lasted for eight nights. (Shabbat 21b). The Talmud also regulates which oils can be used (pretty much anything, including that which can’t be used on Shabbat), how many wicks to light (Shammai says start with 8 and go down to 1 since the days left are fewer, Hillel says to start with 1 and go up to 8 since we “increase in holiness” - Hillel wins), when to light (after dark but while people are still out and about in order to “publicize the miracle”), and where to light (outside, as is still the case in Israel, or at the window, in order to “publicize the miracle”, unless that’s a bad idea in which case inside on a table is fine).

- The Babylonian Talmud also said that one should not use the Chanukah lights for anything, but that it was OK to light another light (pre-electricity, one needed lights to see after dark). This later became the origin of the shamash (Shabbat 21b).

- Additionally, the Babylonian Talmud rules about the blessings to be said when lighting the chanukiah, that we say 3 on the first night and 2 on the other nights (Shabbat 23a). The blessing for Shabbat candles comes from the one for Chanukah candles, and is first recorded in the siddur of Amram Gaon (800s CE).

- The chanukiah in Talmudic times was also made from clay or stone, or sometimes metal, and had 8 holes for wicks.

- In the 1200s in Spain, chanukiot evolved again, with a back on it, eight dimples for oil, and a shamash for the first time (on a different plane from the others). These were meant to be hung on the wall.

- In medieval Germany it was popular to have an 8-pointed star chanukiah which hung from the ceiling (an example is in the Sarajevo Haggadah).

- In the 1800s, candles became mass-produced and thus affordable for the masses.

- In the 1940s, brass chanukiot are mass-produced.

- In the Holocaust (1933-1945, when money was scarce and then freedom was scarcer), many Jews made chanukiot out of potatoes, a dab of butter, and a thread.

- In the 1960s, electric chanukiot are mass-produced (and onwards)

- Nowadays, technically one should light the Shammash, then say the blessings, then start lighting the candles, and while doing so sing “Hanerot Hallalu” (which comes from Sofrim 20:6, a text from the 700s CE).

6. What’s the Story Behind Latkes?

- Latkes are potato pancakes fried in oil to remember the rekindling of the menorah (or the miracle of the oil)

- Coincidentally, the Judean olive harvest finished right around the 25th of Kislev, when Chanukah starts.

- The story begins 600 years before Chanukah, when the Assyrians were threatening the Israelites. According the Book of Judith (in the Apocrypha, written after the Bible was closed), Judith seduced the Assyrian general (Holofernes) with salty cheese and wine; when he fell asleep she cut off his head with his own sword, thus saving the Jewish people.

-There was some confusion about Assyrians vs. Syrians, and Judith sounded a bit like Judah, so in the 1300s Italian Jews began making fried ricotta cheese pancakes to eat on Chanukah. These were called “cassola” and were served with fruit preserves.

- In Eastern Europe, olive oil was super-expensive, so the frying agent of choice was goose fat (geese were being slaughtered in the winter, so goose fat was plentiful and cheap). If you keep kosher you can’t fry cheese pancakes in goose fat, so the pancakes became buckwheat ones (supposedly what the Maccabees ate, and also suspiciously similar to Russian blini).

- By the 1600s, potatoes had migrated from the South American Andes to Europe (leading to the Irish Famine of 1848). Over the next 200 more years they went from animal feed to prison food to plentiful food for the masses, especially during the winter. - This led to Eastern European potato pancakes in the 1800s, which were called “latkes” in Yiddish (“Levivot” in Hebrew). Latkes elevated the usual boiled or mashed potatoes into a “grate” holiday treat.

- Sour cream dates to the early 1900s, when it became possible to keep milk into the winter (since animals mostly have milk in the spring)

- In 1927, “latke” first entered the Oxford English Dictionary.

- Sephardic latke recipes included zucchini and garlic rather than potatoes and onions; the yogurt topping is omitted when served with meat.

- Other recipes collected by Leah Koenig include: spinach (Mediterranean), curried sweet potato (modern America), meat and herb (Syria), chard (North Africa), rice (contemporary Italy), and chicken (or fish), scallion, and ginger (India)

- Latkes are another example of how the Syrian-Greeks wanted us to adapt the surrounding culture and disappear, and instead we’ve adapted the surrounding culture to thrive as Jews.

- Coincidentally, the Judean olive harvest finished right around the 25th of Kislev, when Chanukah starts.

- The story begins 600 years before Chanukah, when the Assyrians were threatening the Israelites. According the Book of Judith (in the Apocrypha, written after the Bible was closed), Judith seduced the Assyrian general (Holofernes) with salty cheese and wine; when he fell asleep she cut off his head with his own sword, thus saving the Jewish people.

-There was some confusion about Assyrians vs. Syrians, and Judith sounded a bit like Judah, so in the 1300s Italian Jews began making fried ricotta cheese pancakes to eat on Chanukah. These were called “cassola” and were served with fruit preserves.

- In Eastern Europe, olive oil was super-expensive, so the frying agent of choice was goose fat (geese were being slaughtered in the winter, so goose fat was plentiful and cheap). If you keep kosher you can’t fry cheese pancakes in goose fat, so the pancakes became buckwheat ones (supposedly what the Maccabees ate, and also suspiciously similar to Russian blini).

- By the 1600s, potatoes had migrated from the South American Andes to Europe (leading to the Irish Famine of 1848). Over the next 200 more years they went from animal feed to prison food to plentiful food for the masses, especially during the winter. - This led to Eastern European potato pancakes in the 1800s, which were called “latkes” in Yiddish (“Levivot” in Hebrew). Latkes elevated the usual boiled or mashed potatoes into a “grate” holiday treat.

- Sour cream dates to the early 1900s, when it became possible to keep milk into the winter (since animals mostly have milk in the spring)

- In 1927, “latke” first entered the Oxford English Dictionary.

- Sephardic latke recipes included zucchini and garlic rather than potatoes and onions; the yogurt topping is omitted when served with meat.

- Other recipes collected by Leah Koenig include: spinach (Mediterranean), curried sweet potato (modern America), meat and herb (Syria), chard (North Africa), rice (contemporary Italy), and chicken (or fish), scallion, and ginger (India)

- Latkes are another example of how the Syrian-Greeks wanted us to adapt the surrounding culture and disappear, and instead we’ve adapted the surrounding culture to thrive as Jews.

7. What’s the Story Behind Sufganiyot?

- North African Jews ate sweet fried balls of dough on Chanukah, which they called “sfenj”.

- By the year 1000 CE, Maimonides’ father (Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef) said not to make fun of eating these “sofganim”, because it is a custom of “the ancient ones” (kadmonim). “Sofganim” came from the Talmudic term for “spongy”.

- In 1485, a Nuremberg cookbook (one of the first printed on a printing press) published the first recipe for jam-filled doughnuts. Until this time, doughnuts were savory. In the 1500s, Caribbean sugar plantations made sugar available for not much money, so sweet doughnuts became a thing.

- Sugar made fruit preserves possible, so jelly doughnuts spread across Northern Europe as a holiday treat. In German they became Berliners, in Polish they became paczki (flower buds), and in Yiddish they became ponchiks (fried in goose fat or oil instead of lard).

- In the early 1900s, Polish and German Jews brought the idea of ponchiks on Chanukah to the Land of Israel, where they met the North African sfenj. The doughnut became called the “sufganiyah”.

- In Bukhara in Central Asia, where Jews have lived since Persian Jews fled there in the 400s CE, the story was that Adam and Eve were given jam-filled doughnuts by G-d after being kicked out of the Garden of Eden and these were called “Sof Gan Y-H” (end of the Garden of G-d); really it’s a new word.

- Bukharan Jews also derive life lessons from sufganiyot: 1. It’s round like the wheel of fortune, so one who is on “bottom” in life today might be on “top” of life tomorrow 2. The inside is more interesting than the outside, so don’t judge people by appearances 3. You never know what kind you are getting until you take a bite, so don’t try to predict the future.

- In 1920, Russian-Jewish Adolph Levitt invented the modern doughnut-making machine in New York City as WWI veterans had such a demand for European “fried dough” that he couldn’t make them by hand fast enough.

- In the 1920s, the Histadrut (national labor union in the Land of Israel) pushed for sufganiyot to become more widespread. The reason is that latkes could be made at home, while sufganiyot provided jobs to Jewish bakers.

- In the 1970s, American Jews who visited or studied in Israel, as well as Israeli Jews who were in the US, started to popularize sufganiyot in the United States.

- In the 1980s, Argentinian immigrants brought dulce de leche to Israel, and it joined jam and chocolate as a popular filling for sufganiyot.

- 100 years after the Histadrut’s efforts to popularize sufganiyot, Israelis now eat 18 million sufganiyot each year.

- By the year 1000 CE, Maimonides’ father (Rabbi Maimon ben Yosef) said not to make fun of eating these “sofganim”, because it is a custom of “the ancient ones” (kadmonim). “Sofganim” came from the Talmudic term for “spongy”.

- In 1485, a Nuremberg cookbook (one of the first printed on a printing press) published the first recipe for jam-filled doughnuts. Until this time, doughnuts were savory. In the 1500s, Caribbean sugar plantations made sugar available for not much money, so sweet doughnuts became a thing.

- Sugar made fruit preserves possible, so jelly doughnuts spread across Northern Europe as a holiday treat. In German they became Berliners, in Polish they became paczki (flower buds), and in Yiddish they became ponchiks (fried in goose fat or oil instead of lard).

- In the early 1900s, Polish and German Jews brought the idea of ponchiks on Chanukah to the Land of Israel, where they met the North African sfenj. The doughnut became called the “sufganiyah”.

- In Bukhara in Central Asia, where Jews have lived since Persian Jews fled there in the 400s CE, the story was that Adam and Eve were given jam-filled doughnuts by G-d after being kicked out of the Garden of Eden and these were called “Sof Gan Y-H” (end of the Garden of G-d); really it’s a new word.

- Bukharan Jews also derive life lessons from sufganiyot: 1. It’s round like the wheel of fortune, so one who is on “bottom” in life today might be on “top” of life tomorrow 2. The inside is more interesting than the outside, so don’t judge people by appearances 3. You never know what kind you are getting until you take a bite, so don’t try to predict the future.

- In 1920, Russian-Jewish Adolph Levitt invented the modern doughnut-making machine in New York City as WWI veterans had such a demand for European “fried dough” that he couldn’t make them by hand fast enough.

- In the 1920s, the Histadrut (national labor union in the Land of Israel) pushed for sufganiyot to become more widespread. The reason is that latkes could be made at home, while sufganiyot provided jobs to Jewish bakers.

- In the 1970s, American Jews who visited or studied in Israel, as well as Israeli Jews who were in the US, started to popularize sufganiyot in the United States.

- In the 1980s, Argentinian immigrants brought dulce de leche to Israel, and it joined jam and chocolate as a popular filling for sufganiyot.

- 100 years after the Histadrut’s efforts to popularize sufganiyot, Israelis now eat 18 million sufganiyot each year.

8. What’s the Story Behind “Maoz Tzur”?

- “Maoz Tzur” has 6 stanzas (surprise!), 5 of which were written in late 1100s on the banks of the Rhine River and the last of which was written in the 1500s.

- The first 5 stanzas form an acrostic spelling out the name “Mordechai”, which is assumed to be the author’s name (and thought to be Mordechai ben Isaac).

- The first stanza is well-known. The next 4 refer to persecutions: Egypt, Babylonia, Persia (Haman), and Chanukah. The last one asks G-d to avenge us (probably due to our historically oppressed role).

- For all the verses, see here: https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/206624?lang=bi.

- By 1450, the common tune (“The German tune”, sometimes considered a “MiSinai tune” because it is so old that it was thought to come “from Sinai”) was in use by Jews - it was adapted from several German folk songs (as put together by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, the father of Jewish musicology).

- We know this because in 1450, Baruch ben Samson from Arweiler (modern Germany) wrote to a choir conductor that the conductor should use the “Maoz Tzur” tune for the new poem he wrote.

- In the late 1400s, there is a Bohemian folk song that is similar to the origin-songs for “Maoz Tzur” and this leads to a Bohemian version of “Maoz Tzur” which is a little different from the usual German tune (according to an 1820 manuscript in the Israel National Library)

- In 1523, the same German folk tune was used by Martin Luther for his German chorale "Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g'mein" (you can hear it in this lecture: https://youtu.be/q4QMkPqWATs at 20:49).

- In 1560, the first printed version of these words appear in a siddur (from Salonica, Greece).

- In 1724, Benedetto Marcello (a Christian) published another tune (“the Italian tune”) that had been used for “Maoz Tzur.” It was in use by the Tedesco (German Jews in Italy) community. Marcello was writing new Church music based on Jewish tunes, considering them to be more authentic to the Early Church, and he published this tune to show his sources. In the National Library of Israel the tune is attributed to him as the composer.

- Also in the 1700s, the tune for “Eili Tziyon” (based on “The Women of Weissenburg”) was so popular in Europe that it got set to other things including “Maoz Tzur.”

- In 1744, Judah Elias of Hanover (modern Germany) publishes sheet music with the “German tune” of “Maoz Tzur” (Baroque-ified - see the YouTube video at 27:13) set to psalms sung in the synagogue on Chanukah.

- In the 1800s, as Jews were accepted into European society during the Enlightenment, they self-censored the last verse (asking G-d to bring judgement on the Christians for their persecutions) and translated the song into nicer language (starting with the 1871 German translation).

- Also in the 1800s, Julius Mombach, the cantor in London’s Great Synagogue, modified the tune of the “German tune” (specifically the end of the repeat of the first section - see the same YouTube link, at 24:12, to hear this) - this is still how British Jews sing it today.

- German Jews brought “Maoz Tzur” to the United States in the 1800s.

- In 1897, Marcus Jastrow (of Talmud dictionary fame) writes “Rock of Ages”, a translation of “Maoz Tzur” in English for American Jews. “Rock of Ages” is first published in the Union Hymnal of the Reform Movement.

- In 1927, Israel Goldfarb (composer of the tune for “Shalom Aleichem” and “V’shamru” among many prayers) publishes “Maoz Tzur” with only the first and fifth stanzas (the ones having to do with Chanukah) along with “Rock of Ages”.

- In 1937, Harry Coopersmith of Anshe Emet (Emeth) Synagogue in Chicago includes “Maoz Tzur” in his “Songs of My People”, which is widely distributed in Hebrew Schools around America. This spreads the song and cements its popularity for the holiday in America.

- In 1942, Joachim Stutschewsky attempts to popularize the “Italian tune” in Israel on grounds that the “German tune” is based on German folksongs and thus isn’t Jewish enough. This effort succeeds in the 1940’s and 50’s. Thereafter, both tunes were used.

- “Maoz Tzur” spread to non-Ashkenazi Jewish communities as they encountered it in Israel and America.

- The first 5 stanzas form an acrostic spelling out the name “Mordechai”, which is assumed to be the author’s name (and thought to be Mordechai ben Isaac).

- The first stanza is well-known. The next 4 refer to persecutions: Egypt, Babylonia, Persia (Haman), and Chanukah. The last one asks G-d to avenge us (probably due to our historically oppressed role).

- For all the verses, see here: https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/206624?lang=bi.

- By 1450, the common tune (“The German tune”, sometimes considered a “MiSinai tune” because it is so old that it was thought to come “from Sinai”) was in use by Jews - it was adapted from several German folk songs (as put together by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, the father of Jewish musicology).

- We know this because in 1450, Baruch ben Samson from Arweiler (modern Germany) wrote to a choir conductor that the conductor should use the “Maoz Tzur” tune for the new poem he wrote.

- In the late 1400s, there is a Bohemian folk song that is similar to the origin-songs for “Maoz Tzur” and this leads to a Bohemian version of “Maoz Tzur” which is a little different from the usual German tune (according to an 1820 manuscript in the Israel National Library)

- In 1523, the same German folk tune was used by Martin Luther for his German chorale "Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g'mein" (you can hear it in this lecture: https://youtu.be/q4QMkPqWATs at 20:49).

- In 1560, the first printed version of these words appear in a siddur (from Salonica, Greece).

- In 1724, Benedetto Marcello (a Christian) published another tune (“the Italian tune”) that had been used for “Maoz Tzur.” It was in use by the Tedesco (German Jews in Italy) community. Marcello was writing new Church music based on Jewish tunes, considering them to be more authentic to the Early Church, and he published this tune to show his sources. In the National Library of Israel the tune is attributed to him as the composer.

- Also in the 1700s, the tune for “Eili Tziyon” (based on “The Women of Weissenburg”) was so popular in Europe that it got set to other things including “Maoz Tzur.”

- In 1744, Judah Elias of Hanover (modern Germany) publishes sheet music with the “German tune” of “Maoz Tzur” (Baroque-ified - see the YouTube video at 27:13) set to psalms sung in the synagogue on Chanukah.

- In the 1800s, as Jews were accepted into European society during the Enlightenment, they self-censored the last verse (asking G-d to bring judgement on the Christians for their persecutions) and translated the song into nicer language (starting with the 1871 German translation).

- Also in the 1800s, Julius Mombach, the cantor in London’s Great Synagogue, modified the tune of the “German tune” (specifically the end of the repeat of the first section - see the same YouTube link, at 24:12, to hear this) - this is still how British Jews sing it today.

- German Jews brought “Maoz Tzur” to the United States in the 1800s.

- In 1897, Marcus Jastrow (of Talmud dictionary fame) writes “Rock of Ages”, a translation of “Maoz Tzur” in English for American Jews. “Rock of Ages” is first published in the Union Hymnal of the Reform Movement.

- In 1927, Israel Goldfarb (composer of the tune for “Shalom Aleichem” and “V’shamru” among many prayers) publishes “Maoz Tzur” with only the first and fifth stanzas (the ones having to do with Chanukah) along with “Rock of Ages”.

- In 1937, Harry Coopersmith of Anshe Emet (Emeth) Synagogue in Chicago includes “Maoz Tzur” in his “Songs of My People”, which is widely distributed in Hebrew Schools around America. This spreads the song and cements its popularity for the holiday in America.

- In 1942, Joachim Stutschewsky attempts to popularize the “Italian tune” in Israel on grounds that the “German tune” is based on German folksongs and thus isn’t Jewish enough. This effort succeeds in the 1940’s and 50’s. Thereafter, both tunes were used.

- “Maoz Tzur” spread to non-Ashkenazi Jewish communities as they encountered it in Israel and America.

With appreciation to: MyJewishLearning.com, HaAretz, Aish, JewishMag, ReformJudaism.org, The Forward, Sarah Jaffa Kasden, LearnReligions.com, Smithsonian Magazine, ChowHound.com, Rabbi Deborah Prinz, Temple Israel of Westchester, HanukkahGelt.com, The American Israelite, Time Magazine, PBS.org, The Takeout, The Atlantic, Wikipedia, Gil Marks, GaspWorthySups, Hebrew University, Eric Kimmel’s A Chanukah Treasury.

Appendix A: Chanukah Customs From Around the World (via MyJewishLearning, B’chol Lashon, Cherie Karo Schwartz’ My Lucky Dreidel*, and Reudor’s The Hebrew Months Tell Their Story)

1. North Africa, Greece, and the Middle East - Chag HaBanot / The Festival of Women / Eid al-Bnat - on Rosh Chodesh Tevet, girls and women don’t work and gather to celebrate the story of Judith. They eat sweets and fried treats, sing into the night, and go to the synagogue to kiss the Torah. In Eastern Europe, women do not have to work on the first or last nights of Chanukah in remembrance of Judith.

2. North Africa and the Middle East - no work while the candles are lit - since the candles aren’t to be used for anything besides enjoying them, there is a custom that while the candles are lit women don’t do any work that they couldn’t do on Shabbat.

3. Morocco - 9th night of Chanukah - during the 8th day of Chanukah, children gather the leftover cotton wicks, and then the community makes a large bonfire to celebrate the end of Chanukah together. This also happened in Germany with the leftover wicks and oil.*

4. Yemen - celebration of Hannah - the 7th night is set aside for as a women’s holiday in celebration of Hannah, who gave up her 7 sons as martyrs to G-d

5. Ethiopia and India - historically no Chanukah - the communities were isolated before Chanukah became a holiday, so they didn’t know about Chanukah until they reunited with the rest of the Jewish people in the 20th century.

6. Morocco - fasting on the last day of Chanukah and not talking all day to make up for anything that they might have said that was not peaceful.*

7. Greece - girls on the seventh night try to make peace with friends or relatives whom they might have wronged.*

8. North Africa - in the past, women went to the synagogue on the seventh night of Chanukah and could hold Torah scrolls for the only time of the year.*

9. Aden, Yemen - children wear blue on Chanukah (because blue is the color of the heavens, from whence miracles come), and recreate the battle of the Maccabees.*

10. Poland - Hasidic Jews used to collect enough food, clothing, and wood (for heating and cooking) to last poor households for a year, as well as collect money for Jews wrongfully imprisoned and for yeshiva students studying away from home.*

11. Eastern Europe - a feast on the fifth night to celebrate the triumph of light over darkness, because now there are more candles lit than not (not including the shamash)

12. Kurdistan - children carry dolls of Antiochus and then set them on fire at night

13. Modi’in (Israel) - on the first night a torch is lit at the Maccabee family tomb, then carried by relay runner to Jerusalem and throughout Israel*

14. Yemen - lighting firecrackers at night in the street to provide additional light (and sound)*

15. Venice - Jewish families would ride through the streets on gondolas, looking for houses with chanukiyot to stop and sing Chanukah songs at*

16. Eastern Europe - fathers of brides-to-be would give future sons-in-law gifts on Chanukah to welcome them into the family*

17. Eastern Europe - children would receive a coin from their parents, and then go to their other relatives to wish them Happy Chanukah and receive more coins.*

18. Morocco - women would tell each other stories each night of the holiday*

19. Eastern Europe - playing card games with Jewish heroes as the "face cards"*

20. Middle East - morning picnics with lots of games*

21. Eastern Europe - in the 1800s and early 1900s, children would be asked riddles or questions about their studies (or about Chanukah traditions)*

22. Many countries - gifts or services are offered to family members, women, teachers, synagogue caretakers, and the poor to offer friendship and peace*

23. Israel - Today the Maccabiah (Jewish Olympics) take place on Chanukah*

Appendix B: Chanukah Candle Customs From Around the World (via MyJewishLearning, B’chol Lashon, Cherie Karo Schwartz’ My Lucky Dreidel*, and Reudor’s The Hebrew Months Tell Their Story)

1. Northern Africa - Hanging the chanukiah near the mezuzah - (North African menorahs have a ring on top and a flat metal back, and this is done to protect the house. This is based on the Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 22a.

2. Romania and Austria - using potatoes to make the chanukiah - Each potato is carved out to have space for oil and a wick, and you add a potato each night. This dates to a time of economic hardship.

3. Aleppo (Syria) - an extra shamash each night - either to honor G-d or their non-Jewish neighbors who welcomed them when they were refugees from Spain.

4. Israel - outdoor chanukiah aquariums - per the Talmud (Shabbat 21b) saying that the chanukiah should be outside for all to see, the glass box keeps the wind from blowing out the lights

5. Alsace (France) - Double-decker chanukiot - to allow multiple people to light at the same time.

6. Afghanistan - oil plates - when Persian Jews fled to Afghanistan in 1839, they weren’t sure how their neighbors would feel about public displays of Jewishness, so they put 8 plates with some oil together. If somebody visited who wasn’t friendly, the plates could be put around the house.

7. Jerusalem - chanukiah cut-outs in buildings - before the glass box was developed, buildings were made with a special spot on the outside for putting a menorah.

8. Syria - parents give their children a candle in the shape of a hand (hamsa) to protect them from the evil eye.

9. Middle East - Egg-shell chanukiot - nine egg shells filled with oil, so that the light shone through the shells*.

10. Egypt - lighting during the day too - because a light in the day was more unusual than a light at night, they would light candles in the synagogue in the morning without a blessing to remind people how many candles to light at night in their homes*

11. Holocaust - butter candles - when resources were scarce in the ghettos and concentration camps, Jews would make candles/oil out of fat or butter, with wicks from threads and a chanukiyah from an old potato*

12. Syria - rather than use a shamash candle, the shamash (caretaker of the synagogue) would give each family a decorated candle to light the others and then he was paid*

13. Syria - Other Jews, whose families came from Spain in the 1400s, have a chanukiyah with 2 shammash candles as a reminder of the protection that led those Jews to Syria (until they had to flee Syria also)*

14. Tunisia - The chanukiyah is hung on the doorpost opposite the mezuzah until Purim to remind of the rededication of the lights*

15. Eastern Europe - the synagogue caretaker makes Chanukah candles out of the drippings from the Yom Kippur memorial candles*

16. Turkey - make new candles from the Chanukah wax drippings to have a candle to search for chametz before Passover*

17. Morocco - the chanukiyah has 5 hamsas (hands) and 2 doves that point to the shamash above the oil holders*

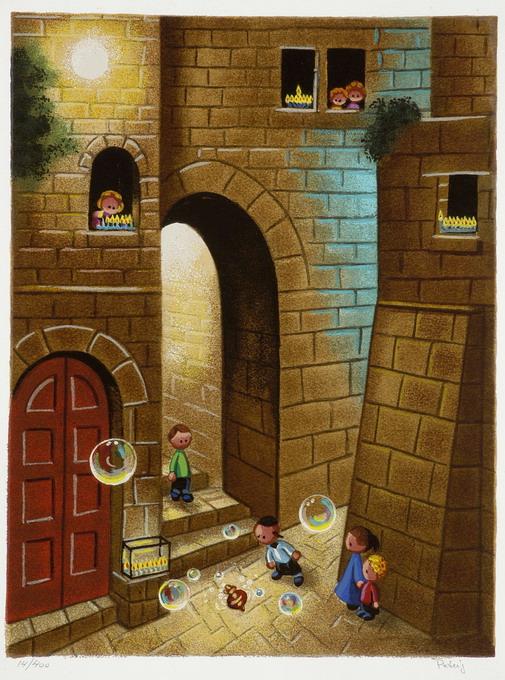

This art by “Peter G” shows the box around the chanukiah in Jerusalem. “Peter G” is Peter Gandolfi, who has been painting in Jerusalem since 1986. His work is often characterized by bubbles.

https://safrai.com/product-category/peterg/

Appendix C: Chanukah Food Customs From Around the World (via MyJewishLearning, B’chol Lashon, Cherie Karo Schwartz’ My Lucky Dreidel*, and Reudor’s The Hebrew Months Tell Their Story)

1. Southern India - Eating gulab jamnun - this is a milk-based ball of dough that is deep-fried and drenched in sugar syrup (also consumed by non-Jewish Indians during Diwali)

2. Avignon (France) - neighborhood wine tastings - the Saturday night of Chanukah, each family opens a bottle of local wine and makes a toast to the miracles of Chanukah, then visits other families to see what bottles they chose.

3. Colombia - eating fried plantains - a new custom by Chavurat Shirat Hayyam

4. Morocco - Sfenj - fried doughnuts with the zest and juice of an orange. Jaffa oranges come into season around this time, so oranges became associated with Chanukah.

5. Hebron - there is a celebration on the last night of Chanukah where the women eat macaroni and salty cheese (in honor of Judith) and spend the evening together talking and telling each other stories.

6. India - eating fried cakes called neyyapam.*

7. Yemen - children bring carrots, roasted corn, and grape juice to Hannnukah parties*

8. Persian Jews - On the last night the children get a tray of fruit and nuts to share in school the next day, as a reminder of what the Maccabees ate in their caves*

9. Salonika (Greece) - women make loukoumades (loo-koo-MAH-dehs), Greek honey doughnut balls, on grounds that the Maccabees probably ate those*

10. Syria - Kibbeh (Middle Eastern meatballs in a crunchy casing) are served to remind us that the Maccabees ate food inside caves*

11. Spain - On the 6th night women make a sweet couscous dish, as a reminder of the sweet freedom many Spanish Jews found in the Middle East/North Africa after 1492.*

12. Many countries - Food and supplies are gathered for the poor on Chanukah*

13. Sephardim in Jerusalem - children go house to house asking for ingredients - beans, onions, oil, garlic, rice. Then they take everything to the synagogue and parade around the bima 7 times with kettles of food on their head. Next they make a feast ("Miranda de Hanukah") for the orphans, widows, and poor and the kids receive meat pies to thank them for helping others.*

14. Many countries - foods with cheese are eaten in memory of the story of Judith (like latkes with cottage cheese, cheese kugel, cheese blintzes, and cheesecake*

Appendix D: Some Chanukah Songs

This is the “German tune”, sung by Kol Sasson, the University of Maryland Jewish a cappella group, in 2014.

This is the “Italian tune”, sung by Makela DC, a young professional Jewish a cappella group.

This is a mash-up of “I have a little dreidel”, “Mi Yimalel”, and “Maoz Tzur” (German tune), by Shir Soul a cappella, a professional Jewish a cappella group in New York City.

This is the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, led by Lori Lippitz, singing “Ocho Kandelikas”, a Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) Chanukah song written by Flory Jagoda. The foods described in it, like almond pastries with honey, were served at supervised teen Chanukah parties that Flory experienced as a youth. Teens were supposed to date, so this was their opportunity to meet each other. (Kippah tip to Cantor Neil Schwartz, who studied with Flory).

This is “Oh Chanukah Oh Chanukah” in English, Hebrew, and Yiddish (Judea-German), sung by NJBeats, the Tulane University Jewish a cappella group.

This is “Hanerot Hallalu”, the complete version (Abraham Tzvi Davidowitz tune), sung by Eli of “Jewish Music Toronto”.

This is “Sevivon Sov Sov Sov”, sung in a Big Band style by Kenny Ellis.

This is the Maccabeats (a cappella) singing a latke recipe parody of “Shut Up and Dance With Me”.

This is Six13 (an a cappella group) singing Chanukah lyrics to Star Wars songs.

This is Six13 singing Chanukah lyrics to West Side Story music.

Appendix E: Another Origin Story for Latkes

Ben Aronin (1904-1980), known as "Uncle Ben" was the Jewish educator / B'nai Mitzvah tutor at Anshe Emet Synagogue in Chicago, primarily in the 1940s-70s. He was an author, playwright, camp director, TV series producer, and songwriter. His most famous song is "The Ballad of the Four Sons". This song (jokingly) posits another origin story for latkes.

The Latke Ditty

Words by: Ben Aronin.

Melody: O Chanukah, O Chanukah!

Words by: Ben Aronin.

Melody: O Chanukah, O Chanukah!

Each Chanukah we glorify brave Judah Maccabeus

Who had the courage to defy Antiochus and free us.

Yet, it is not fair that we should forget

Mrs. Maccabeus, whom we owe a debt.

Who had the courage to defy Antiochus and free us.

Yet, it is not fair that we should forget

Mrs. Maccabeus, whom we owe a debt.

She mixed it. She fixed it. She poured it into a bowl.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That gave brave Judah a soul.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That gave brave Judah a soul.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That gave brave Judah a soul.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That gave brave Judah a soul.

Now, this is how it came about, this gastronomic wonder

That broke the ranks of Syria like flaming bolts of thunder.

Mrs. Maccabeus wrote in the dough,

portions of the Torah and then fried them so.

That broke the ranks of Syria like flaming bolts of thunder.

Mrs. Maccabeus wrote in the dough,

portions of the Torah and then fried them so.

They simmered. They shimmered, absorbing the olive oil.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That made the Syrians recoil.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That made the Syrians recoil.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That made the Syrians recoil.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes

That made the Syrians recoil.

The Syrians said, “It cannot be that old Mattathias

Whose years are more than eighty three, would dare to defy us.”

But they did not know his secret, you see

Mattathias dined on latkes and tea.

Whose years are more than eighty three, would dare to defy us.”

But they did not know his secret, you see

Mattathias dined on latkes and tea.

One latke, two latkes, and so on into the night.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

That gave them the courage to fight.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

That gave them the courage to fight.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

That gave them the courage to fight.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

That gave them the courage to fight.

And so each little latke, brown and delicious

Must have hit the spot, for with appetite viscous

All the heroes ate them after their toil

Causing in the Temple a shortage of oil.

Must have hit the spot, for with appetite viscous

All the heroes ate them after their toil

Causing in the Temple a shortage of oil.

One latke, two latkes, and so on into the night.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

that gave us the Chanukah light.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

that gave us the Chanukah light.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

that gave us the Chanukah light.

You may not guess, but it was the latkes,

that gave us the Chanukah light.

www.tintCleveland.org/page/Chanukah/The-Latke-Ditty.aspx

Appendix F: The Composers of Some Chanukah SongsAccording to My Lucky Dreidel, by Cherie Karo Schwartz

- “I Have a Little Dreidel” (originally “My Dreydl”) = words by Samuel Grossman

- “Rock of Ages” = English words by Gustav Gottheil and Marcus Jastrow

- “Mi Yemalel” = Hebrew words by Menashe Ravino; English words by Ben M. Edidin (original English lyrics = Who can retell the things that befell us? / Who can count them? / In ev’ry age a hero or sage came to our aid! / Hark! In days of yore, in Israel’s ancient land, / Brave Maccabeus led the faithful band. / But now all Israel must as one arise, / Redeem itself through deed and sacrifice. /